Sunday, July 20, 2008

James Brown's stuff for sale

Bow-tied auctioneer John Hayes soon became the hardest-working man in the auction business when a medical bracelet etched with the words "JAMES BROWN ALLERGY PENICILLIN DIABETIC" set off the day’s first bidding war: Estimated at $200–$300, for some odd reason it skyrocketed to $26,000. One disappointed bidder for the bracelet was Paul Shaffer, who also lost out on a set of red-leather living-room furniture, estimated at $1,500–$2,000, which went for $32,000. But the third time was the charm for Shaffer, whose $8,000 bid won him Brown’s Hammond B3 organ and Leslie speaker cabinet.

Bow-tied auctioneer John Hayes soon became the hardest-working man in the auction business when a medical bracelet etched with the words "JAMES BROWN ALLERGY PENICILLIN DIABETIC" set off the day’s first bidding war: Estimated at $200–$300, for some odd reason it skyrocketed to $26,000. One disappointed bidder for the bracelet was Paul Shaffer, who also lost out on a set of red-leather living-room furniture, estimated at $1,500–$2,000, which went for $32,000. But the third time was the charm for Shaffer, whose $8,000 bid won him Brown’s Hammond B3 organ and Leslie speaker cabinet.As a number of the so-called "sex suits" were about to go on sale, the intro to “Get Up (I Feel Like Being A) Sex Machine” piped into the room, providing a rare moment of funkiness in Christie’s rather staid Rockefeller Center confines. “And now the Sex Machine belt,” Hayes said, deadpanning. “I’ve waited my entire life to say that.” Including Christie's premium, the belt sold for $4,750.

Posted at NYmag.com

Thursday, July 03, 2008

Call Me James: How I Met the Godfather

This article appears in the upcoming issue of Heeb. It's about my unusual relationship with James Brown. I also have a story, originally published by Down Beat in 1980, in The James Brown Reader: 50 Years of Writing About the Godfather of Soul.

Here's the Heeb piece:

My first meeting with James Brown was not going well.

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” he screamed at me inside a suite in New York City’s swank Sherry Netherland Hotel in 1979. “It would be best if you don’t do too much speaking and do more listening. You don’t know what I’m saying. You don’t know anything about soul music.”

What apparently set Brown off was a comment I had made about disco being much more arranged than, for instance, a song like “Sex Machine.”

Despite his short stature, James Brown was incredibly imposing. He’d been a prizefighter as a teenager in Georgia during the late ’40s and early ’50s, so perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised when he lashed out at me.

“New York is nothin’ about soul music,” Brown spit. “It’s about what’s left of it. You got to go down South to cut your records, bro.” “What about Motown?” I asked.

“What about Motown?” I asked.

“Motown was never soul. It was pop,” he replied.

“And what’s disco?” I asked.

“It’s a vamp of good soul music, but disco can’t stay ’cause it has no arrangements. You said it was arranged. You don’t understand it. You’ll understand it in another five years.”

Then he delivered the knockout shot: “You don’t know nothing about music, bro. Cut the interview off.”

With that, he pushed the stop button on my tape recorder and our session was over.

I wasn’t gay, black, Hispanic or Italian, but by the late ’70s, I had fallen in love with disco. I bought loud shirts and tight pants and walked around with a boom box. Yes, I was that funky white boy. So while everyone at the SoHo Weekly News fought over who was going to cover the next punk band playing at the Mudd Club party, I was given a column called “Rhythm & Bloom,” which led to my James Brown assignment. Being a funky, Jewish, white boy sometimes pays off.  I was into Brown’s ’60s hits, “I Got You” and “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” but it was the Hot Pants album of 1971 that really gave me a hard-on. Admittedly, I hopped aboard his soul train a little late, but I played catch-up with a vengeance. I began collecting his albums—Brown released over a hundred—and got hooked on the smartly arranged horns, chicken-scratch guitar, thumping bass and syncopated drums that defined his music and the black music of America at the time. The Godfather of Soul released four albums a year from 1968 to 1972, and produced numerous solo acts on his People label.

I was into Brown’s ’60s hits, “I Got You” and “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” but it was the Hot Pants album of 1971 that really gave me a hard-on. Admittedly, I hopped aboard his soul train a little late, but I played catch-up with a vengeance. I began collecting his albums—Brown released over a hundred—and got hooked on the smartly arranged horns, chicken-scratch guitar, thumping bass and syncopated drums that defined his music and the black music of America at the time. The Godfather of Soul released four albums a year from 1968 to 1972, and produced numerous solo acts on his People label.

But by the late ’70s, Brown was no longer relevant in the black community and was viewed as an oldies act among many whites. Record sales ebbed and Brown’s wealth dried up.

I went back to the hotel the next day, hoping he’d give our interview another shot. I was nervous given the agitated state I left him in, but Brown didn’t seem to remember our discussion the night before. He sat patiently under a dryer with his straightened dark hair in curlers as I peppered him with softballs about the plight of the ghetto.

“I can hug and kiss you for the questions you are asking me today,” he said, startling me. “I love you for that, and I appreciate it. I really do. You can probably see the water in my eyes for giving me the opportunity to say this without arguin’ and fightin’ because this thing is going to get across to people."

“See, I ain’t never been down against white people because I know they’re the best friends blacks have ever had.” Then Brown smiled at me. “Well, Jewish people have been more helpful because they taught blacks about their rights. The Anglo-Saxon, or whatever you call them, didn’t teach the blacks no rights. He is guilty of that.”

Maybe it was my last name or maybe it was my nose or maybe it was just part of the crazy stream of consciousness that was flowing from his lips that day, but somehow Brown had ascertained that I was Jewish. Or so it seemed.

He went back and forth from subject to subject furiously during that meeting, recommending that blacks go back to the land (“Stay in the country and leave society alone.”), praising the white R&B band Tower of Power (“There’s no black group that plays my stuff as good as them.”) and warning about his upcoming shows at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem (“If they mug you white people, then I’m through. I’ll never come back. It doesn’t make sense because there’s nothing that white people like more than black entertainment.”).

As the interview wound down, Brown picked up a phone and dialed MCA Records: “This is James Brown, the entertainer. Let me speak to the President.” He was forwarded to the A&R department and they invited him to stop by.

Next thing I knew I was in the elevator heading down to the lobby with Brown and his entourage. As we hit the street, people stopped in their tracks. Short, dark, muscular and wearing a cowboy hat, Brown was unmistakable.

Two sneaker-clad black teens that weren’t even 8 years old when “Hot Pants” came out stopped and stared incredulously. “James Motherfucking Brown,” one yelled out.

“James Motherfucking Brown,” one yelled out.

Brown climbed into limo. He told me to get in and I did.

“MCA Records!” Brown barked to the driver.

“It’s at 55th and Park,” I added.

Brown placed his hand on my shoulder. “You know, Steve, I need a bright young Jewish man like you in the organization.”

That topped it all. Less than 24 hours after Brown had bolted from my interview, he was offering me a job—undoubtedly the greatest Jewish moment since my bar mitzvah.

“You got a pretty good story here, Steve, right?”

“Yessir, Mr. Brown,” I replied. (All of the members of his band and entourage called him Mr. Brown.)

“You don’t have to call me Mr. Brown,” he said. “You can call me James.”

From that moment forward, I had access to Brown straight through the ’80s. Any time he played New York City or nearby, I was invited backstage where I was permitted to conduct impromptu interviews before and after shows and during intermissions.

Unfortunately, as time went on, I saw him less and less, even though our bond was solid as a rock. “There’s so much more I want to do,” Brown told me in 1988. “I want to do a country album. I want to do a gospel album. I want to do a jazz album….” Then he looked directly at me with a sly grin. “And I want to do a Yiddish album too. Shalom!

I don’t want to make too big a deal of James Brown’s closeness to Judaism, but I know that he enjoyed jiving me about it. In hindsight, I wonder whether some of his fondness for the Jews came from his relationships with his original manager Ben Bart and King record label president Sid Nathan. Wherever it came from, it was part of the story of our friendship. I imagine there weren’t just a few fellow music journalists who marveled at how I had infiltrated the James Brown camp.

Sunday, June 08, 2008

You Don't Mess With the Zohan

A Rambo-like Israeli army special-ops soldier with superhuman powers, Zohan leaves hero status behind to follow his dream of becoming a hair stylist in New York. Faking his death and defeat to The Phantom (a silly John Turturro), the film playfully transitions from discord in the Middle East to Zohan's ability to “make sticky” with a parade of delirious elderly women (see the Sandler-produced Grandma’s Boy for another example of these perverse pairings) at a beauty parlor run by Dalia (Entourage's Emmanuelle Chriqui), who’s Palestinian.

A Rambo-like Israeli army special-ops soldier with superhuman powers, Zohan leaves hero status behind to follow his dream of becoming a hair stylist in New York. Faking his death and defeat to The Phantom (a silly John Turturro), the film playfully transitions from discord in the Middle East to Zohan's ability to “make sticky” with a parade of delirious elderly women (see the Sandler-produced Grandma’s Boy for another example of these perverse pairings) at a beauty parlor run by Dalia (Entourage's Emmanuelle Chriqui), who’s Palestinian.Written by Sandler, Judd Apatow and Robert Smigel, Zohan has plenty of raunchy gags to spare — such as a game of cat hacky sack — but the movie ultimately bogs down as Zohan pursues Dalia, and The Phantom arrives for a showdown with his comic-book rival. Cameos by Mariah Carey, Henry Winkler, Kevin Nealon and George Takai add little to the story, though Chris Rock’s patois-chatting cab driver is a momentary hoot.

While diehard Sandler fans will trace Zohan's desire to change the world by making hair "silky smooth" to Billy Madison, they’ll have to settle for a lukewarm, feel-good resolution that’s a metaphor for ending the conflict in the Middle East.

Posted at TheLMagazine.com

Friday, April 04, 2008

Shine A Light

The doc begins with Martin Scorsese frantically trying to find out what the show’s set list is going to be. After a full-throttle “Jumping Jack Flash” opener, three special guests are introduced at various points: while Jack White nervously duets with Mick Jagger on “Loving Cup,” Buddy Guy injects genuine blues ferocity to Muddy Waters’s “Champagne & Reefer” and Christina Aquilera climbs octaves on “Live With Me.”

The doc begins with Martin Scorsese frantically trying to find out what the show’s set list is going to be. After a full-throttle “Jumping Jack Flash” opener, three special guests are introduced at various points: while Jack White nervously duets with Mick Jagger on “Loving Cup,” Buddy Guy injects genuine blues ferocity to Muddy Waters’s “Champagne & Reefer” and Christina Aquilera climbs octaves on “Live With Me.”Quick cuts and extreme close-ups capture Jagger awkwardly shimmying about the stage and catwalk, and Keith Richards joyfully leading the 13-piece band (including backup singers and horns). In addition, Scorsese intersperses archival interview footage between songs. Towards the end of the 18-song set, the Stones’ signature centerpiece “Sympathy for the Devil” falls flat as the audience chants “ooh ooh.” But “Brown Sugar” – again, with the crowd loudly wooing along – is a rousing finale.

Shine a Light provides a backstage pass to rock and roll nostalgia of the highest order. It’s the nature of the game.

Posted at TheLMagazine.com

Friday, March 28, 2008

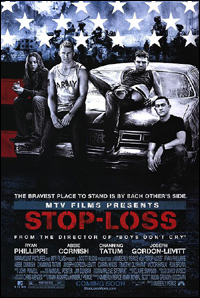

Stop-Loss

Singe never complained about being in Baghdad. When his tour ended, he came home and, probably before he kissed his relatives, sparked up a joint. Little did he know he would be drug tested shortly thereafter. Singe failed the test and was ordered back to Iraq. He had been "stop-lossed."

I never heard the term until I saw Kimberly Peirce's movie Stop-Loss earlier this month at the SXSW Film Festival. The movie, which opens today, is about three U.S. soldiers who come home after a devastating tour in Iraq. They're all suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, but each deals with their problems in a different way. Brandon (Ryan Phillippe) is a sergeant who's haunted by an ambush that killed and maimed several of his men - including ambush survivors Steve (Channing Tatum) and Tommy (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), who predictably act out in several drunken, violent scenes in their Texas small town.

Then Brandon finds out he's being stop-lossed. Despite his loyalty to the Army, Brandon fights back, hoping to overturn this arbitrary decision. In the movie, it's described as a "backdoor draft." Quietly, the military finds any number of reasons to reenlist soldiers, as they did with Singe, because they simply need bodies to hold down the fort in Iraq.

Brandon takes off on a road trip to Washington, where he hopes a Congressman will come to his aid. But now he's branded a deserter and no one will touch him. It's a classic Catch-22 scenario.

He's joined on the drive by Michele (Abbie Cornish), who's engaged to Steve and lives with Brandon's parents. (The Australian Cornish starred with Heath Ledger in the junkie love story, Candy.) You keep expecting them to get romantic, but this never happens. (In real life, they reportedly did get involved, causing his breakup with Reese Witherspoon.) Finally, after considering crossing into Canada or Mexico, Brandon heads back to Texas, defeated.

The dramatic finale with Brandon and Steve coming to blows and wrestling homoerotically is an unnecessary exclamation point on this explosive story.

After the screening, Peirce took questions from the approving audience. I asked if she's heard of soldiers being stop-lossed after failing drug tests. The director drew a blank. Unlike Brandon, Singe willfully returned to Iraq. He's one patriotic stoner.

Friday, March 21, 2008

Drillbit Taylor

With Judd Apatow co-producing and Seth Rogen co-writing, the jokes come fast and furious, but still can’t help the formulaic plot. Wilson’s Drillbit is a homeless vet hired by high-school frosh (Danny McBride, Josh Peck and David Dorfman) to be their bodyguard. His stint as a substitute teacher is straight out of School of Rock, just less hilarious. Rather than spending so much time with him coaching the kids, the film could have focused more on Drillbit’s budding relationship with Lisa (Leslie Mann of Knocked Up and Apatow’s wife) - the goldielocked duo generate sparks - and subdued the traditional revenge message. But that would have been a different and, more likely, better movie.

With Judd Apatow co-producing and Seth Rogen co-writing, the jokes come fast and furious, but still can’t help the formulaic plot. Wilson’s Drillbit is a homeless vet hired by high-school frosh (Danny McBride, Josh Peck and David Dorfman) to be their bodyguard. His stint as a substitute teacher is straight out of School of Rock, just less hilarious. Rather than spending so much time with him coaching the kids, the film could have focused more on Drillbit’s budding relationship with Lisa (Leslie Mann of Knocked Up and Apatow’s wife) - the goldielocked duo generate sparks - and subdued the traditional revenge message. But that would have been a different and, more likely, better movie.For Wilson, it’s time for him to leave the Drillbit Taylors of the world behind. His next role as journalist/dog lover John Grogan in Marley and Me (with Jennifer Aniston and a Golden Retriever) looks promising.

Posted at LMagazine.com

Saturday, February 09, 2008

Strange Wilderness

Guaranteed to be among the Worst Movies of 2008, Fred Wolf's raunchy stoner comedy should have been shot with a tranquilizer dart rather than released on Super Bowl Weekend. This send-up of nature shows starring Steve Zahn, Jonah Hill, Allen Covert and Justin Long has little going for it except for a few bong hits (by Long), joint pulls (Zahn, Covert) and a zany road trip.

Guaranteed to be among the Worst Movies of 2008, Fred Wolf's raunchy stoner comedy should have been shot with a tranquilizer dart rather than released on Super Bowl Weekend. This send-up of nature shows starring Steve Zahn, Jonah Hill, Allen Covert and Justin Long has little going for it except for a few bong hits (by Long), joint pulls (Zahn, Covert) and a zany road trip.Unfortunately there are few laughs along the way as the crew tracks Bigfoot - unless you consider a turkey clamping down on Zahn's pecker for an extending bit hilarious. That's about as good as it gets.

Though I love stoner movies, I can't in good conscience recommend Strange Wilderness.

Posted at CelebStoner

Vince Vaughn's Wild West Comedy Show

Sans the star of Swingers and Wedding Crashers, few people would have ponied up cash for Vaughn’s faux-variety show. The lanky actor emcees and performs occasional skits. One with special guests John Favreau and Justin Long doing shtick from Swingers is the highlight, and it comes within the first 10 minutes. Another during a stop in Bakersfield features a tone-deaf Vaughn crooning alongside country singer Dwight Yoakam.

Sans the star of Swingers and Wedding Crashers, few people would have ponied up cash for Vaughn’s faux-variety show. The lanky actor emcees and performs occasional skits. One with special guests John Favreau and Justin Long doing shtick from Swingers is the highlight, and it comes within the first 10 minutes. Another during a stop in Bakersfield features a tone-deaf Vaughn crooning alongside country singer Dwight Yoakam.Unlike the talented Comedians of Comedy cast, the stand-ups here are mediocre at best. While Egyptian-American Ahmed Ahmed has the edginess of someone who’s endured the worst of racial profiling since 9/11, John Caparulo, Bret Ernst and Sebastian Maniscalco are fairly indistinguishable, with Caparulo’s crude cursing setting him apart as the least entertaining of the minor-league bunch.

Another questionable element to this whole undertaking is the tour’s timing. The first show takes place in Los Angeles on September 12, 2005, less than two weeks after Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast. A visit to a trailer camp in Alabama shows their concern, but perhaps the tour should have been postponed (or, better yet, canceled). Intended for a 2006 release, Vaughn’s Wild West Comedy Show is dated, vain and, worst of all, not funny.

Posted at TheLMagazine.com